All materials in these studies that are not otherwise attributed are © 2014 by Tool Box for Faith. Expressed permission is hereby granted to download and print these materials for personal/congregational use only. If you wish to use any of these materials for any other groups or other purposes, please contact us (gennowdisciples@gmail.com) for permission. In all cases, include this copyright notice and email address with any versions of the material. Thank you.

Section 1: Opening Prayer

Section 2: A Reformer, not a Protestant

The event that sparked the Reformation seems fairly insignificant in an age of social media-based complaints: some guy made a list of 95 things he didn’t like about the church and stuck them on the church door. In fact, this was a very common thing to do 500 years ago. The way to start a public conversation was to post something where everyone would show up, and would do so in crowds. What better place in 16th century Wittenberg than the Castle Church doors? Luther did this, and focused these particular critiques on the sale of indulgences, which were ways for people to ensure quicker access into heaven for their dead loved ones. Luther also sent the 95 Theses to the Archbishop Albert of Mainz, the regional authority of the Roman Catholic Church. This caught the interest of a local indulgence preacher, Johann Tetzel, which led to a war of words between himself and Luther that ultimately led to Luther’s excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church in 1521.

Now, this section is about Luther and not just the 95 Theses or his excommunication. We start with this simply to point out what most of the world knows about Luther. He started the Reformation by complaining about Catholic sale of indulgences. That’s entirely true, and yet there’s so much more to this man. There’s a coming of age story, where he’s not sure what he wants to be when he grows up. There’s a story of insecurity, of a man not sure that he was worthy of level or his role as a priest. There’s the story of person who was fully saint and sinner, for his good theological convictions led to an awakening of the church to God’s gracious spirit even as prejudice overflowed in some of his writings, which led to complicity in atrocities against people in poverty and Jewish people.

One key thing to understand about Martin Luther is that his intent was never to start a new church. Luther desired to reform the Roman Catholic Church, which is why he sent his comments to Archbishop Albert and tried to start a local conversation.He wasn’t trying to protests from without, but rather reform from within. Luther didn’t leave Catholicism until he was kicked out of the church, and even then, he understood his movement as the faithful continuation of true Catholicism.

Before we go on, check out this brief intro to Luther’s life.

Section 3:

For a wonderfully entertaining overview of Luther’s leadership in the Reformation, watch this video until about 8:22 (the end of a reference to the Avengers).

Like many of us, Luther felt torn between the call he felt in his own life and what his parents expected of him. Martin’s father Hans knew hard work as a miner and then a smelter, someone who extracts the valuable minerals from the less valuable rocks around them. However, Hans wanted Luther to have a more lucrative and less physically demanding career, so he paved the way for Martin to become a lawyer. He got as far as a Master of Arts degree before, in a terrible thunderstorm, Martin felt a fear like nothing he’d ever known. He cried out to St. Anne, the Patron Saint of Miners, for her favor, even going so far as to say that if he lived through the storm he’d become a monk.

Yet, his development as a priest and monk did not resolve the sense of anxiety in his life. Martin became more distraught, not just of his own sin, but in fear that God could never love him. His confessor, Johann Staupitz, was so weary of Luther’s confession of insignificant trespasses that Staupitz sent Luther away until he had something “interesting” to share. Luther’s profound understanding of God’s Law not only led to personal distress; it eventually led to his appointment as a theology professor at the university in Wittenberg.

It was during this time as a professor that he posted the 95 Theses, which led to his dialogue with Tetzel. This culminated in the Diet of Worms, which was a referendum by Charles the V, Holy Roman Emperor, on Luther’s ideas. After presenting his case, Luther stated that his mind was bound by “reason” and “holy scripture,” then concluded with that now famous line: “Here I stand; I can do no other. God help me.” The Edict of Worms, Charles V’s final response, declared Luther a heretic with the authority of Pope Leo X.

From here, Luther went into hiding under the protection of Frederick the Wise at Wartburg Castle. Here Luther began another controversial project: translating the Bible into common German so that all people could read scripture for themselves. This eventually leads to even more reforms, including worship in German language, which first happened in 1525 at the first official Protestant worship service.

While Luther’s heart as a reformer sought God, some of his personal prejudices proved unholy. For instance, when poor, oppressed people in Germany saw the practical application of Luther’s Freedom of a Christian, they used it in their revolt to secure more rights and freedom from the rich who controlled much of their lives. Luther, however, wrote a work called, “Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants,” in which sided with the wealthy landowners and spoke of theological freedom as primarily a spiritual concept and having little to do with social organization. This lent the church’s authority to the state’s massacre of over 100,000 peasants.

Similarly, Luther initially sought to make more healthy relationships with Jews in Germany.Martin once thought Jews would see God’s fullness in Jesus once the Reformation took hold. However, as he grew older and saw the church fracturing rather than uniting, he became disenchanted. Though he had lifelong issues with constipation (yep – Luther had poop problems), Luther blamed a bad bout of food poisoning on a Jewish cook and wrote a terrible book called, “On the Jews and Their Lies.” Antisemitism and antijudaism were already common in Germany, but this once again lent spiritual credence to social prejudice.

We tell these stories to be honest about Luther. He started perhaps the most significant movement in the last 500 years, transforming the church and society in powerfully positive ways. Yet, he remained a sinner and captive to his time. His support for the wealthy landowners was likely tied to his loyalty to Frederick the Wise, the rich lord who protected Luther when the Holy Roman Empire sought to take his life. His early life saw movement away from the common bigotry toward Jews in his day, but he proved too weak to truly break free from that discriminatory attitude.

Perhaps the most telling story of Luther’s life is when he led worship for the first time as a priest. As he lifted the cup during communion, he spilled the wine. This was not just a messy mistake for 16th century Catholics, for at this point, it was believed to be the true blood of Christ. In the eyes of many, he’d dumped Jesus onto the dirty floor. Already frightened at his own sinfulness, his father only further added to the anxiety, suggesting that Luther had peed himself in front of God and humanity. That’s the kind of man Luther was, one desperately wanting to do something significant and yet making mistakes. Some, like his father, could not look passed the spilled wine.

As Lutheran Christians, however, our response should not be to throw out all of Luther’s ministry with his faults. Instead, we ought to name them as the sinful realities they are and then work toward the spiritual ideals that reflect God’s truth. We ought to work beyond Luther’s own limitations – for instance, recognizing that Christian freedom is meaningful in spiritual, social, and physical ways, and that God’s presence in Christ don’t negate God’s promises to the people of Israel. We ought to recognize the sinner that he was, be thankful for the saint that he was, and use that legacy as a guide for how to be more faithful and humble as God’s people.

Section 4: Reformed and Always Reforming

One of the central principles of the reformation adopted not just by Lutherans, but also many other Christians, is that we’re called to be people who are reformed and always reforming. What does this mean? Simply this. Just because we acquire some new clarity about the Gospel at a certain point in our lives doesn’t mean that we fully understand everything about God. Just because we’ve made some thing better doesn’t mean we’re perfect. So, while we embrace our reformation roots, we also realize that we can’t be satisfied with incomplete progress.

It’s that principle that allows us to call ourselves Lutherans. While we embrace the theological reforms that Martin Luther brought, we also recognize he didn’t go nearly far enough in his understanding of Christian freedom or his comprehension for God’s work with Israel and Jewish people throughout history. We remain Lutherans as a part of our Reformation ancestry, but we also recognize Luther’s faults or the limitations on his own work as a reformer. He’s not perfect, nor were his reforms, and yet through him, the Holy Spirit inspired a legacy of reforming the church to more accurately reflect the God that we serve.

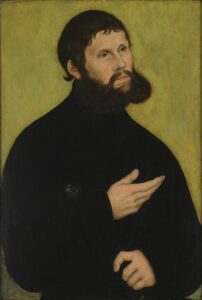

Consider the winky Luther image to the right, which appears throughout The Lutheran Handbook series. It’s an image that reflects a popular picture of Martin Luther from the Reformation, but with a spin that the artists thought was fun. No doubt, it’s pretty entertaining. Yet, does that mean someone should never create their own image of Luther? Does this last reform on a classic image mean the original was inherently bad? No to both! Rather, it’s a reform of the original to make it accessible to a certain audience (teenagers in 2005, to be exact). Only twelve years later, the internet’s popularity is only growing. With it, so are our imaginations for how we can present images of Luther (like memes, YouTube videos like the ones you’ve watched, and even Playmobil toys). Reform is good not just for yesterday, but for tomorrow as well.

With that in mind, answer these questions:

- What part of the Reformation are you most thankful for? Send a tweet to your confirmation teacher or post it on their Facebook wall.

- Where do you think the church still needs to reform itself? Propose an idea to your peers and your pastor and ask how you can work together to make the church more accurately mirror Jesus to the world.

Section 5: Closing Prayer

Opening and Closing Prayers from Sundays and Seasons.com. Copyright 2017 Augsburg Fortress. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission under Augsburg Fortress Liturgies Annual License #25165.